Jim Carrey, Maharishi University, 2014

Billy Kanoi, Hawaii Pacific University, 2014

Tim Minchin, University of Western Australia, 2013

George Saunders, Syracuse University, 2013

Neil Gaiman, University of the Arts, 2012

“The Affect You Have On Others”

Jim Carrey is an actor and comedian of tremendous range and intellect, a man who turns himself inside out for his audiences, who embraces the opportunity of being entirely yourself while profoundly honoring the needs of others.

Thank you Bevan, thank you all!

I brought one of my paintings to show you today. Hope you guys are gonna be able see it okay. It’s not one of my bigger pieces. You might wanna move down front — to get a good look at it. (kidding)

Faculty, Parents, Friends, Dignitaries… Graduating Class of 2014, and all the dead baseball players coming out of the corn to be with us today. (laughter) After the harvest there’s no place to hide — the fields are empty — there is no cover there! (laughter)

I am here to plant a seed that will inspire you to move forward in life with enthusiastic hearts and a clear sense of wholeness. The question is, will that seed have a chance to take root, or will I be sued by Monsanto and forced to use their seed, which may not be totally “Ayurvedic.” (laughter)

Excuse me if I seem a little low energy tonight — today — whatever this is. I slept with my head to the North last night. (laughter) Oh man! Oh man! You know how that is, right kids? Woke up right in the middle of Pitta and couldn’t get back to sleep till Vata rolled around, but I didn’t freak out. I used that time to eat a large meal and connect with someone special on Tinder. (laughter)

Life doesn’t happen to you, it happens for you. How do I know this? I don’t, but I’m making sound, and that’s the important thing. That’s what I’m here to do. Sometimes, I think that’s one of the only things that are important. Just letting each other know we’re here, reminding each other that we are part of a larger self. I used to think Jim Carrey is all that I was…

Just a flickering light

A dancing shadow

The great nothing masquerading as something you can name

Dwelling in forts and castles made of witches – wishes! Sorry, a Freudian slip there

Seeking shelter in caves and foxholes, dug out hastily

An archer searching for his target in the mirror

Wounded only by my own arrows

Begging to be enslaved

Pleading for my chains

Blinded by longing and tripping over paradise – can I get an “Amen”?! (applause)

You didn’t think I could be serious did ya’? I don’t think you understand who you’re dealing with! I have no limits! I cannot be contained because I’m the container. You can’t contain the container, man! You can’t contain the container! (laughter)

I used to believe that who I was ended at the edge of my skin, that I had been given this little vehicle called a body from which to experience creation, and though I couldn’t have asked for a sportier model, (laughter) it was after all a loaner and would have to be returned. Then, I learned that everything outside the vehicle was a part of me, too, and now I drive a convertible. Top down wind in my hair! (laughter)

I am elated and truly, truly, truly excited to be present and fully connected to you at this important moment in your journey. I hope you’re ready to open the roof and take it all in?! (audience doesn’t react) Okay, four more years then! (laughter)

I want to thank the Trustees, Administrators and Faculty of MUM for creating an institution worthy of Maharishi’s ideals of education. A place that teaches the knowledge and experience necessary to be productive in life, as well as enabling the students, through Transcendental Meditation and ancient Vedic knowledge to slack off twice a day for an hour and a half!! (laughter) — don’t think you’re fooling me!!! — (applause) but, I guess it has some benefits. It does allow you to separate who you truly are and what’s real, from the stories that run through your head.

You have given them the ability to walk behind the mind’s elaborate set decoration, and to see that there is a huge difference between a dog that is going to eat you in your mind and an actual dog that’s going to eat you. (laughter) That may sound like no big deal, but many never learn that distinction and spend a great deal of their lives living in fight or flight response.

I’d like to acknowledge all you wonderful parents — way to go for the fantastic job you’ve done — for your tireless dedication, your love, your support, and most of all, for the attention you’ve paid to your children. I have a saying, “Beware the unloved,” because they will eventually hurt themselves… or me! (laughter)

But when I look at this group here today, I feel really safe! I do! I’m just going to say it — my room is not locked! My room is not locked! (laughter) No doubt some of you will turn out to be crooks! But white-collar stuff — Wall St. ya’ know, that type of thing — crimes committed by people with self-esteem! Stuff a parent can still be proud of in a weird way. (laughter)

And to the graduating class of 2017 — minus 3! You didn’t let me finish! (laughter) — Congratulations! (applause) Yes, give yourselves a round of applause, please. You are the vanguard of knowledge and consciousness; a new wave in a vast ocean of possibilities. On the other side of that door, there is a world starving for new leadership, new ideas.

I’ve been out there for 30 years! She’s a wild cat! (laughter) Oh, she’ll rub up against your leg and purr until you pick her up and start pettin’ her, and out of nowhere she’ll swat you in the face. Sure it’s rough sometimes but that’s OK, ‘cause they’ve got soft serve ice cream with sprinkles! (laughter) I guess that’s what I’m really here to say; sometimes it’s okay to eat your feelings! (laughter)

Fear is going to be a player in your life, but you get to decide how much. You can spend your whole life imagining ghosts, worrying about your pathway to the future, but all there will ever be is what’s happening here, and the decisions we make in this moment, which are based in either love or fear.

So many of us choose our path out of fear disguised as practicality. What we really want seems impossibly out of reach and ridiculous to expect, so we never dare to ask the universe for it. I’m saying, I’m the proof that you can ask the universe for it — please! (applause) And if it doesn’t happen for you right away, it’s only because the universe is so busy fulfilling my order. It’s party size! (laughter)

My father could have been a great comedian, but he didn’t believe that was possible for him, and so he made a conservative choice. Instead, he got a safe job as an accountant, and when I was 12 years old, he was let go from that safe job and our family had to do whatever we could to survive.

I learned many great lessons from my father, not the least of which was that you can fail at what you don’t want, so you might as well take a chance on doing what you love. (applause)

That’s not the only thing he taught me though: I watched the affect my father’s love and humor had on the world around me, and I thought, “That’s something to do, that’s something worth my time.”

It wasn’t long before I started acting up. People would come over to my house and they would be greeted by a 7 yr old throwing himself down a large flight of stairs. (laughter) They would say, “What happened?” And I would say, “I don’t know — let’s check the replay.” And I would go back to the top of the stairs and come back down in slow motion. (Jim reenacts coming down the stairs in slow-mo) It was a very strange household. (laughter)

My father used to brag that I wasn’t a ham — I was the whole pig. And he treated my talent as if it was his second chance. When I was about 28, after a decade as a professional comedian, I realized one night in LA that the purpose of my life had always been to free people from concern, like my dad. When I realized this, I dubbed my new devotion, “The Church of Freedom From Concern” — “The Church of FFC”— and I dedicated myself to that ministry.

What’s yours? How will you serve the world? What do they need that your talent can provide? That’s all you have to figure out. As someone who has done what you are about to go do, I can tell you from experience, the effect you have on others is the most valuable currency there is. (applause)

Everything you gain in life will rot and fall apart, and all that will be left of you is what was in your heart. My choosing to free people from concern got me to the top of a mountain. Look where I am — look what I get to do! Everywhere I go – and I’m going to get emotional because when I tap into this, it really is extraordinary to me — I did something that makes people present their best selves to me wherever I go. (applause) I am at the top of the mountain and the only one I hadn’t freed was myself and that’s when my search for identity deepened.

I wondered who I’d be without my fame. Who would I be if I said things that people didn’t want to hear, or if I defied their expectations of me? What if I showed up to the party without my Mardi Gras mask and I refused to flash my breasts for a handful of beads? (laughter) I’ll give you a moment to wipe that image out of your mind. (laughter)

But you guys are way ahead of the game. You already know who you are and that peace, that peace that we’re after, lies somewhere beyond personality, beyond the perception of others, beyond invention and disguise, even beyond effort itself. You can join the game, fight the wars, play with form all you want, but to find real peace, you have to let the armor fall. Your need for acceptance can make you invisible in this world. Don’t let anything stand in the way of the light that shines through this form. Risk being seen in all of your glory. (A sheet drops and reveals Jim’s painting. Applause.)

(Re: the painting) It’s not big enough! (kidding) This painting is big for a reason. This painting is called “High Visibility.” (laughter) It’s about picking up the light and daring to be seen. Here’s the tricky part. Everyone is attracted to the light. The party host up in the corner (refers to painting) who thinks unconsciousness is bliss and is always offering a drink from the bottles that empty you; Misery, below her, who despises the light — can’t stand when you’re doing well — and wishes you nothing but the worst; The Queen of Diamonds who needs a King to build her house of cards; And the Hollow One, who clings to your leg and begs, “Please don’t leave me behind for I have abandoned myself.”

Even those who are closest to you and most in love with you; the people you love most in the world can find clarity confronting at times. This painting took me thousands of hours to complete and — (applause) thank you — yes, thousands of hours that I’ll never get back, I’ll never get them back (kidding) — I worked on this for so long, for weeks and weeks, like a mad man alone on a scaffolding — and when I was finished one of my friends said, “This would be a cool black light painting.” (laughter)

So I started over. (All the lights go off in the Dome and the painting is showered with black light.) Whooooo! Welcome to Burning Man! (applause) Some pretty crazy characters right? Better up there than in here. (points to head) Painting is one of the ways I free myself from concern, a way to stop the world through total mental, spiritual and physical involvement.

But even with that, comes a feeling of divine dissatisfaction. Because ultimately, we’re not the avatars we create. We’re not the pictures on the film stock. We are the light that shines through it. All else is just smoke and mirrors. Distracting, but not truly compelling.

I’ve often said that I wished people could realize all their dreams of wealth and fame so they could see that it’s not where you’ll find your sense of completion. Like many of you, I was concerned about going out in the world and doing something bigger than myself, until someone smarter than myself made me realize that there is nothing bigger than myself! (laughter)

My soul is not contained within the limits of my body. My body is contained within the limitlessness of my soul — one unified field of nothing dancing for no particular reason, except maybe to comfort and entertain itself. (applause) As that shift happens in you, you won’t be feeling the world you’ll be felt by it — you will be embraced by it. Now, I’m always at the beginning. I have a reset button called presence and I ride that button constantly.

Once that button is functional in your life, there’s no story the mind could create that will be as compelling. The imagination is always manufacturing scenarios — both good and bad — and the ego tries to keep you trapped in the multiplex of the mind. Our eyes are not only viewers, but also projectors that are running a second story over the picture we see in front of us all the time. Fear is writing that script and the working title is, ‘I’ll never be enough.’

You look at a person like me and say, (kidding) “How could we ever hope to reach those kinds of heights, Jim? How can I make a painting that’s too big for any reasonable home? How do you fly so high without a special breathing apparatus?” (laughter)

This is the voice of your ego. If you listen to it, there will always be someone who seems to be doing better than you. No matter what you gain, ego will not let you rest. It will tell you that you cannot stop until you’ve left an indelible mark on the earth, until you’ve achieved immortality. How tricky is the ego that it would tempt us with the promise of something we already possess.

So I just want you to relax—that’s my job—relax and dream up a good life! (applause) I had a substitute teacher from Ireland in the second grade that told my class during Morning Prayer that when she wants something, anything at all, she prays for it, and promises something in return and she always gets it. I’m sitting at the back of the classroom, thinking that my family can’t afford a bike, so I went home and I prayed for one, and promised I would recite the rosary every night in exchange. Broke it—broke that promise. (laughter)

Two weeks later, I got home from school to find a brand new mustang bike with a banana seat and easy rider handlebars — from fool to cool! My family informed me that I had won the bike in a raffle that a friend of mine had entered my name in, without my knowledge. That type of thing has been happening ever since, and as far as I can tell, it’s just about letting the universe know what you want and working toward it while letting go of how it might come to pass. (applause)

Your job is not to figure out how it’s going to happen for you, but to open the door in your head and when the doors open in real life, just walk through it. Don’t worry if you miss your cue. There will always be another door opening. They keep opening.

And when I say, “life doesn’t happen to you, it happens for you.” I really don’t know if that’s true. I’m just making a conscious choice to perceive challenges as something beneficial so that I can deal with them in the most productive way. You’ll come up with your own style, that’s part of the fun!

Oh, and why not take a chance on faith as well? Take a chance on faith — not religion, but faith. Not hope, but faith. I don’t believe in hope. Hope is a beggar. Hope walks through the fire. Faith leaps over it.

You are ready and able to do beautiful things in this world and after you walk through those doors today, you will only ever have two choices: love or fear. Choose love, and don’t ever let fear turn you against your playful heart.

Thank you. Jai Guru Dev. I’m so honored. Thank you.

Billy Kanoi

Hawaii Pacific University

MAY 21, 2014

Billy Kanoi is the irrepressible Mayor of Hawaii

Tim Minchin

University of Western Australia, Crawley, Australia

September 17, 2013

Tim Minchin of Australia has won worldwide acclaim as a composer, lyricist, comedian, actor and writer.

In darker days I did a corporate gig at a conference for this big company who made and sold accounting software in a bid, I presumed, to inspire their salespeople to greater heights. They’d forked out 12 grand for an inspirational speaker who was this extreme sports guy who had had a couple of his limbs frozen off when he got stuck on a ledge on some mountain. It was weird.

Software salespeople I think need to hear from someone who has had a long successful career in software sales not from an overly optimistic ex-mountaineer.

Some poor guy who had arrived in the morning hoping to learn about sales techniques ended up going home worried about the blood flow to his extremities. It’s not inspirational, it’s confusing. And if the mountain was meant to be a symbol of life’s challenges and the loss of limbs a metaphor for sacrifice, the software guy’s not going to get it, is he? Because he didn’t do an Arts degree, did he? He should have.

Arts degrees are awesome and they help you find meaning where there is none. And let me assure you… there is none. Don’t go looking for it. Searching for meaning is like searching for a rhymes scheme in a cookbook. You won’t find it and it will bugger up your soufflé. If you didn’t like that metaphor you won’t like the rest of it.

Point being I’m not an inspirational speaker. I’ve never ever lost a limb on a mountainside metaphorically or otherwise and I’m certainly not going to give career advice because, well I’ve never really had what most would consider a job. However I have had large groups of people listening to what I say for quite a few years now and it’s given me an inflated sense of self importance.

So I will now, at the ripe old age of 37-point-nine, bestow upon you nine life lessons to echo of course the nine lessons of carols of the traditional Christmas service, which is also pretty obscure.

You might find some of this stuff inspiring. You will definitely find some of it boring and you will definitely forget all of it within a week. And be warned there will be lots of hokey similes and obscure aphorisms which start well but end up making no sense. So listen up or you’ll get lost like a blind man clapping in a pharmacy trying to echo-locate the contact lens fluid.

(crowd laughs) …Looking for my old poetry teacher. Here we go, ready?

One: You don’t have to have a dream. Americans on talent shows always talk about their dreams. Fine if you have something you’ve always wanted to do, dreamed of, like in your heart, go for it. After all it’s something to do with your time, chasing a dream. And if it’s a big enough one it’ll take you most of your life to achieve so by the time you get to it and are staring into the abyss of the meaningless of your achievement you’ll be almost dead so it won’t matter.

I never really had one of these dreams and so I advocate passionate, dedication to the pursuit of short-term goals. Be micro-ambitious. Put your head down and work with pride on whatever is in front of you. You never know where you might end up. Just be aware the next worthy pursuit will probably appear in your periphery, which is why you should be careful of long-term dreams. If you focus too far in front of you you won’t see the shiny thing out the corner of your eye. Right? Good! Advice metaphor… look at me go.

Two: Don’t seek happiness. Happiness is like an orgasm. If you think about it too much it goes away. (crowd laughs) Keep busy and aim to make someone else happy and you might find you get some as a side effect. We didn’t evolve to be constantly content. Contented Homo erectus got eaten before passing on their genes.

Three: Remember it’s all luck. You are lucky to be here. You are incalculably lucky to be born and incredibly lucky to be brought up by a nice family who encouraged you to go to uni. Or if you were born into a horrible family that’s unlucky and you have my sympathy but you are still lucky. Lucky that you happen to be made of the sort of DNA that went on to make the sort of brain which when placed in a horrible child environment would make decisions that meant you ended up eventually graduated uni. Well done you for dragging yourself up by your shoelaces. But you were lucky. You didn’t create the bit of you that dragged you up. They’re not even your shoelaces.

I suppose I worked hard to achieve whatever dubious achievements I’ve achieved but I didn’t make the bit of me that works hard any more than I made the bit of me that ate too many burgers instead of attending lectures when I was here at UWA. Understanding that you can’t truly take credit for your successes nor truly blame others for their failures will humble you and make you more compassionate. Empathy is intuitive. It is also something you can work on intellectually.

Four: Exercise. I’m sorry you pasty, pale, smoking philosophy grads arching your eyebrows into a Cartesian curve as you watch the human movement mob winding their way through the miniature traffic cones of their existence. You are wrong and they are right. Well you’re half right. You think therefore you are but also you jog therefore you sleep therefore you’re not overwhelmed by existential angst. You can’t be can’t and you don’t want to be. Play a sport. Do yoga, pump iron, and run, whatever but take care of your body, you’re going to need it. Most of you mob are going to live to nearly 100 and even the poorest of you will achieve a level of wealth that most humans throughout history could not have dreamed of. And this long, luxurious life ahead of you is going to make you depressed. (audience laughs) But don’t despair. There is correlation between depression and exercise. Do it! Run, my beautiful intellectuals run.

Five: Be hard on your opinions. A famous bon mot asserts opinions are like assholes in that everyone has one. There is great wisdom in this but I would add that opinions differ significantly from assholes in that yours should be constantly and thoroughly examined. (audience laughs) I used to do exams in here (audience laughs)… It’s revenge.

We must think critically and not just about the ideas of others. Be hard on your beliefs. Take them out onto the verandah and hit them with a cricket bat. Be intellectually rigorous. Identify your biases, your prejudices, your privileges. Most of society is kept alive by a failure to acknowledge nuance. We tend to generate false dichotomies and then try to argue one point using two entirely different sets of assumptions. Like two tennis players trying to win a match by hitting beautifully executed shots from either end of separate tennis courts.

By the way, while I have science and arts graduates in front of me please don’t make the mistake of thinking the arts and sciences are at odds with one another. That is a recent, stupid and damaging idea. You don’t have to be unscientific to make beautiful art, to write beautiful things. If you need proof – Twain, Douglas Adams, Vonnegut, McEwan, Sagan and Shakespeare, Dickens for a start. You don’t need to be superstitious to be a poet. You don’t need to hate GM technology to care about the beauty of the planet. You don’t have to claim a soul to promote compassion. Science is not a body of knowledge nor a belief system it’s just a term which describes human kinds’ incremental acquisition of understanding through observation. Science is awesome! The arts and sciences need to work together to improve how knowledge is communicated. The idea that many Australians including our new PM and my distant cousin Nick Minchin believe that the science of anthropogenic global warming is controversial is a powerful indicator of the extent of our failure to communicate. The fact that 30 percent of the people just bristled is further evidence still. (audience laughs) The fact that that bristling is more to do with politics than science is even more despairing.

Six: Be a teacher! Please! Please! Please be a teacher. Teachers are the most admirable and important people in the world. You don’t have to do it forever but if you’re in doubt about what to do be an amazing teacher. Just for your 20s be a teacher. Be a primary school teacher. Especially if you’re a bloke. We need male primary school teachers. Even if you’re not a teacher, be a teacher. Share your ideas. Don’t take for granted your education. Rejoice in what you learn and spray it.

Seven: Define yourself by what you love. I found myself doing this thing a bit recently where if someone asks me what sort of music I like I say, “Well I don’t listen to the radio because pop song lyrics annoy me,” or if someone asks me what food I like I say, “I think truffle oil is overused and slightly obnoxious.” And I see it all the time online – people whose idea of being part of a subculture is to hate Coldplay or football or feminists or the Liberal Party.

We have a tendency to define ourselves in opposition to stuff. As a comedian I make my living out of it. But try to also express your passion for things you love. Be demonstrative and generous in your praise of those you admire. Send thank you cards and give standing ovations. Be pro stuff not just anti stuff.

Eight: Respect people with less power than you. I have in the past made important decisions about people I work with – agents and producers – big decisions based largely on how they treat the wait staff in the restaurants we’re having the meeting in. I don’t care if you’re the most powerful cat in the room, I will judge you on how you treat the least powerful. So there!

Nine: Finally, don’t rush. You don’t need to know what you’re going to do with the rest of your life. I’m not saying sit around smoking cones all day but also don’t panic! Most people I know who were sure of their career path at 20 are having mid-life crises now.

I said at the beginning of this ramble, which is already three-and-a-half minutes long, life is meaningless. It was not a flippant assertion. I think it’s absurd the idea of seeking meaning in the set of circumstances that happens to exist after 13.8 billion years worth of unguided events. Leave it to humans to think the universe has a purpose for them. However I’m no nihilist. I’m not even a cynic. I am actually rather romantic and here’s my idea of romance: you will soon be dead. Life will sometimes seem long and tough and God it’s tiring. And you will sometimes be happy and sometimes sad and then you’ll be old and then you’ll be dead. There is only one sensible thing to do with this empty existence and that is fill it. Not fillet. Fill it. And in my opinion, until I change it, life is best filled by learning as much as you can about as much as you can. Taking pride in whatever you’re doing. Having compassion, sharing ideas, running, being enthusiastic and then there’s love and travel and wine and sex and art and kids and giving and mountain climbing, but you know all that stuff already. It’s an incredibly exciting thing this one meaningless life of yours. Good luck and thank you for indulging me.

“Be Kinder”

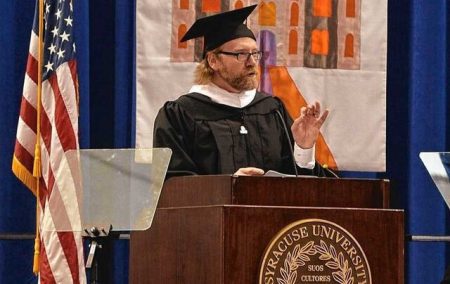

George Saunders

Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York USA

May 11, 2013

George Saunders is an American writer of short stories, essays, novellas and children’s books. A professor at Syracuse, Saunders has received both a MacArthur Fellowship and the PEN/Malamud Award.

Down through the ages, a traditional form has evolved for this type of speech, which is: Some old fart, his best years behind him, who, over the course of his life, has made a series of dreadful mistakes (that would be me), gives heartfelt advice to a group of shining, energetic young people, with all of their best years ahead of them (that would be you).

And I intend to respect that tradition.

Now, one useful thing you can do with an old person, in addition to borrowing money from them, or asking them to do one of their old-time “dances,” so you can watch, while laughing, is ask: “Looking back, what do you regret?” And they’ll tell you. Sometimes, as you know, they’ll tell you even if you haven’t asked. Sometimes, even when you’ve specifically requested they not tell you, they’ll tell you.

So: What do I regret? Being poor from time to time? Not really. Working terrible jobs, like “knuckle-puller in a slaughterhouse?” (And don’t even ASK what that entails.) No. I don’t regret that. Skinny-dipping in a river in Sumatra, a little buzzed, and looking up and seeing like 300 monkeys sitting on a pipeline, pooping down into the river, the river in which I was swimming, with my mouth open, naked? And getting deathly ill afterwards, and staying sick for the next seven months? Not so much. Do I regret the occasional humiliation? Like once, playing hockey in front of a big crowd, including this girl I really liked, I somehow managed, while falling and emitting this weird whooping noise, to score on my own goalie, while also sending my stick flying into the crowd, nearly hitting that girl? No. I don’t even regret that.

But here’s something I do regret:

In seventh grade, this new kid joined our class. In the interest of confidentiality, her Convocation Speech name will be “ELLEN.” ELLEN was small, shy. She wore these blue cat’s-eye glasses that, at the time, only old ladies wore. When nervous, which was pretty much always, she had a habit of taking a strand of hair into her mouth and chewing on it.

So she came to our school and our neighborhood, and was mostly ignored, occasionally teased (“Your hair taste good?” – that sort of thing). I could see this hurt her. I still remember the way she’d look after such an insult: eyes cast down, a little gut-kicked, as if, having just been reminded of her place in things, she was trying, as much as possible, to disappear. After awhile she’d drift away, hair-strand still in her mouth. At home, I imagined, after school, her mother would say, you know: “How was your day, sweetie?” and she’d say, “Oh, fine.” And her mother would say, “Making any friends?” and she’d go, “Sure, lots.”

Sometimes I’d see her hanging around alone in her front yard, as if afraid to leave it.

And then – they moved. That was it. No tragedy, no big final hazing.

One day she was there, next day she wasn’t.

End of story.

Now, why do I regret that? Why, forty-two years later, am I still thinking about it? Relative to most of the other kids, I was actually pretty nice to her. I never said an unkind word to her. In fact, I sometimes even (mildly) defended her.

But still. It bothers me.

So here’s something I know to be true, although it’s a little corny, and I don’t quite know what to do with it:

What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness.

Those moments when another human being was there, in front of me, suffering, and I responded…sensibly. Reservedly. Mildly.

Or, to look at it from the other end of the telescope: Who, in your life, do you remember most fondly, with the most undeniable feelings of warmth?

Those who were kindest to you, I bet.

It’s a little facile, maybe, and certainly hard to implement, but I’d say, as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.

Now, the million-dollar question: What’s our problem? Why aren’t we kinder?

Here’s what I think:

Each of us is born with a series of built-in confusions that are probably somehow Darwinian. These are: (1) we’re central to the universe (that is, our personal story is the main and most interesting story, the only story, really); (2) we’re separate from the universe (there’s US and then, out there, all that other junk – dogs and swing-sets, and the State of Nebraska and low-hanging clouds and, you know, other people), and (3) we’re permanent (death is real, o.k., sure – for you, but not for me).

Now, we don’t really believe these things – intellectually we know better – but we believe them viscerally, and live by them, and they cause us to prioritize our own needs over the needs of others, even though what we really want, in our hearts, is to be less selfish, more aware of what’s actually happening in the present moment, more open, and more loving.

So, the second million-dollar question: How might we DO this? How might we become more loving, more open, less selfish, more present, less delusional, etc., etc?

Well, yes, good question.

Unfortunately, I only have three minutes left.

So let me just say this. There are ways. You already know that because, in your life, there have been High Kindness periods and Low Kindness periods, and you know what inclined you toward the former and away from the latter. Education is good; immersing ourselves in a work of art: good; prayer is good; meditation’s good; a frank talk with a dear friend; establishing ourselves in some kind of spiritual tradition – recognizing that there have been countless really smart people before us who have asked these same questions and left behind answers for us.

Because kindness, it turns out, is hard – it starts out all rainbows and puppy dogs, and expands to include…well,everything.

One thing in our favor: some of this “becoming kinder” happens naturally, with age. It might be a simple matter of attrition: as we get older, we come to see how useless it is to be selfish – how illogical, really. We come to love other people and are thereby counter-instructed in our own centrality. We get our butts kicked by real life, and people come to our defense, and help us, and we learn that we’re not separate, and don’t want to be. We see people near and dear to us dropping away, and are gradually convinced that maybe we too will drop away (someday, a long time from now). Most people, as they age, become less selfish and more loving. I think this is true. The great Syracuse poet, Hayden Carruth, said, in a poem written near the end of his life, that he was “mostly Love, now.”

And so, a prediction, and my heartfelt wish for you: as you get older, your self will diminish and you will grow in love. YOU will gradually be replaced by LOVE. If you have kids, that will be a huge moment in your process of self-diminishment. You really won’t care what happens to YOU, as long as they benefit. That’s one reason your parents are so proud and happy today. One of their fondest dreams has come true: you have accomplished something difficult and tangible that has enlarged you as a person and will make your life better, from here on in, forever.

Congratulations, by the way.

When young, we’re anxious – understandably – to find out if we’ve got what it takes. Can we succeed? Can we build a viable life for ourselves? But you – in particular you, of this generation – may have noticed a certain cyclical quality to ambition. You do well in high-school, in hopes of getting into a good college, so you can do well in the good college, in the hopes of getting a good job, so you can do well in the good job so you can….

And this is actually O.K. If we’re going to become kinder, that process has to include taking ourselves seriously – as doers, as accomplishers, as dreamers. We have to do that, to be our best selves.

Still, accomplishment is unreliable. “Succeeding,” whatever that might mean to you, is hard, and the need to do so constantly renews itself (success is like a mountain that keeps growing ahead of you as you hike it), and there’s the very real danger that “succeeding” will take up your whole life, while the big questions go untended.

So, quick, end-of-speech advice: Since, according to me, your life is going to be a gradual process of becoming kinder and more loving: Hurry up. Speed it along. Start right now. There’s a confusion in each of us, a sickness, really: selfishness. But there’s also a cure. So be a good and proactive and even somewhat desperate patient on your own behalf – seek out the most efficacious anti-selfishness medicines, energetically, for the rest of your life.

Do all the other things, the ambitious things – travel, get rich, get famous, innovate, lead, fall in love, make and lose fortunes, swim naked in wild jungle rivers (after first having it tested for monkey poop) – but as you do, to the extent that you can, err in the direction of kindness. Do those things that incline you toward the big questions, and avoid the things that would reduce you and make you trivial. That luminous part of you that exists beyond personality – your soul, if you will – is as bright and shining as any that has ever been. Bright as Shakespeare’s, bright as Gandhi’s, bright as Mother Theresa’s. Clear away everything that keeps you separate from this secret luminous place. Believe it exists, come to know it better, nurture it, share its fruits tirelessly.

And someday, in 80 years, when you’re 100, and I’m 134, and we’re both so kind and loving we’re nearly unbearable, drop me a line, let me know how your life has been. I hope you will say: It has been so wonderful.

Congratulations, Class of 2013.

I wish you great happiness, all the luck in the world, and a beautiful summer.

Neil Gaiman

University of the Arts, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA

MAY 17, 2012

Mr. Gaiman is an award-winning graphic novelist. This speech has received international acclaim and he recently published it.

I never really expected to find myself giving advice to people graduating from an establishment of higher education. I never graduated from any such establishment. I never even started at one. I escaped from school as soon as I could, when the prospect of four more years of enforced learning before I’d become the writer I wanted to be was stifling.

I got out into the world, I wrote, and I became a better writer the more I wrote, and I wrote some more, and nobody ever seemed to mind that I was making it up as I went along, they just read what I wrote and they paid for it, or they didn’t, and often they commissioned me to write something else for them.

Which has left me with a healthy respect and fondness for higher education that those of my friends and family, who attended Universities, were cured of long ago.

Looking back, I’ve had a remarkable ride. I’m not sure I can call it a career, because a career implies that I had some kind of career plan, and I never did. The nearest thing I had was a list I made when I was 15 of everything I wanted to do: to write an adult novel, a children’s book, a comic, a movie, record an audiobook, write an episode of Doctor Who… and so on. I didn’t have a career. I just did the next thing on the list.

So I thought I’d tell you everything I wish I’d known starting out, and a few things that, looking back on it, I suppose that I did know. And that I would also give you the best piece of advice I’d ever got, which I completely failed to follow.

First of all: When you start out on a career in the arts you have no idea what you are doing.

This is great. People who know what they are doing know the rules, and know what is possible and impossible. You do not. And you should not. The rules on what is possible and impossible in the arts were made by people who had not tested the bounds of the possible by going beyond them. And you can.

If you don’t know it’s impossible it’s easier to do. And because nobody’s done it before, they haven’t made up rules to stop anyone doing that again, yet.

Secondly, if you have an idea of what you want to make, what you were put here to do, then just go and do that.

And that’s much harder than it sounds and, sometimes in the end, so much easier than you might imagine. Because normally, there are things you have to do before you can get to the place you want to be. I wanted to write comics and novels and stories and films, so I became a journalist, because journalists are allowed to ask questions, and to simply go and find out how the world works, and besides, to do those things I needed to write and to write well, and I was being paid to learn how to write economically, crisply, sometimes under adverse conditions, and on time.

Sometimes the way to do what you hope to do will be clear cut, and sometimes it will be almost impossible to decide whether or not you are doing the correct thing, because you’ll have to balance your goals and hopes with feeding yourself, paying debts, finding work, settling for what you can get.

Something that worked for me was imagining that where I wanted to be – an author, primarily of fiction, making good books, making good comics and supporting myself through my words – was a mountain. A distant mountain. My goal.

And I knew that as long as I kept walking towards the mountain I would be all right. And when I truly was not sure what to do, I could stop, and think about whether it was taking me towards or away from the mountain. I said no to editorial jobs on magazines, proper jobs that would have paid proper money because I knew that, attractive though they were, for me they would have been walking away from the mountain. And if those job offers had come along earlier I might have taken them, because they still would have been closer to the mountain than I was at the time.

I learned to write by writing. I tended to do anything as long as it felt like an adventure, and to stop when it felt like work, which meant that life did not feel like work.

Thirdly, when you start off, you have to deal with the problems of failure. You need to be thickskinned, to learn that not every project will survive. A freelance life, a life in the arts, is sometimes like putting messages in bottles, on a desert island, and hoping that someone will find one of your bottles and open it and read it, and put something in a bottle that will wash its way back to you: appreciation, or a commission, or money, or love. And you have to accept that you may put out a hundred things for every bottle that winds up coming back.

The problems of failure are problems of discouragement, of hopelessness, of hunger. You want everything to happen and you want it now, and things go wrong. My first book – a piece of journalism I had done for the money, and which had already bought me an electric typewriter from the advance – should have been a bestseller. It should have paid me a lot of money. If the publisher hadn’t gone into involuntary liquidation between the first print run selling out and the second printing, and before any royalties could be paid, it would have done.

And I shrugged, and I still had my electric typewriter and enough money to pay the rent for a couple of months, and I decided that I would do my best in future not to write books just for the money. If you didn’t get the money, then you didn’t have anything. If I did work I was proud of, and I didn’t get the money, at least I’d have the work.

Every now and again, I forget that rule, and whenever I do, the universe kicks me hard and reminds me. I don’t know that it’s an issue for anybody but me, but it’s true that nothing I did where the only reason for doing it was the money was ever worth it, except as bitter experience. Usually I didn’t wind up getting the money, either. The things I did because I was excited, and wanted to see them exist in reality have never let me down, and I’ve never regretted the time I spent on any of them.

The problems of failure are hard.

The problems of success can be harder, because nobody warns you about them.

The first problem of any kind of even limited success is the unshakable conviction that you are getting away with something, and that any moment now they will discover you. It’s Imposter Syndrome, something my wife Amanda christened the Fraud Police.

In my case, I was convinced that there would be a knock on the door, and a man with a clipboard (I don’t know why he carried a clipboard, in my head, but he did) would be there, to tell me it was all over, and they had caught up with me, and now I would have to go and get a real job, one that didn’t consist of making things up and writing them down, and reading books I wanted to read. And then I would go away quietly and get the kind of job where you don’t have to make things up any more.

The problems of success. They’re real, and with luck you’ll experience them. The point where you stop saying yes to everything, because now the bottles you threw in the ocean are all coming back, and have to learn to say no.

I watched my peers, and my friends, and the ones who were older than me and watch how miserable some of them were: I’d listen to them telling me that they couldn’t envisage a world where they did what they had always wanted to do any more, because now they had to earn a certain amount every month just to keep where they were. They couldn’t go and do the things that mattered, and that they had really wanted to do; and that seemed as a big a tragedy as any problem of failure.

And after that, the biggest problem of success is that the world conspires to stop you doing the thing that you do, because you are successful. There was a day when I looked up and realised that I had become someone who professionally replied to email, and who wrote as a hobby. I started answering fewer emails, and was relieved to find I was writing much more.

Fourthly, I hope you’ll make mistakes. If you’re making mistakes, it means you’re out there doing something. And the mistakes in themselves can be useful. I once misspelled Caroline, in a letter, transposing the A and the O, and I thought, “Coraline looks like a real name…”

And remember that whatever discipline you are in, whether you are a musician or a photographer, a fine artist or a cartoonist, a writer, a dancer, a designer, whatever you do you have one thing that’s unique. You have the ability to make art.

And for me, and for so many of the people I have known, that’s been a lifesaver. The ultimate lifesaver. It gets you through good times and it gets you through the other ones.

Life is sometimes hard. Things go wrong, in life and in love and in business and in friendship and in health and in all the other ways that life can go wrong. And when things get tough, this is what you should do.

Make good art.

I’m serious. Husband runs off with a politician? Make good art. Leg crushed and then eaten by mutated boa constrictor? Make good art. IRS on your trail? Make good art. Cat exploded? Make good art. Somebody on the Internet thinks what you do is stupid or evil or it’s all been done before? Make good art. Probably things will work out somehow, and eventually time will take the sting away, but that doesn’t matter. Do what only you do best. Make good art.

Make it on the good days too.

And fifthly, while you are at it, make your art. Do the stuff that only you can do.

The urge, starting out, is to copy. And that’s not a bad thing. Most of us only find our own voices after we’ve sounded like a lot of other people. But the one thing that you have that nobody else has is you. Your voice, your mind, your story, your vision. So write and draw and build and play and dance and live as only you can.

The moment that you feel that, just possibly, you’re walking down the street naked, exposing too much of your heart and your mind and what exists on the inside, showing too much of yourself. That’s the moment you may be starting to get it right.

The things I’ve done that worked the best were the things I was the least certain about, the stories where I was sure they would either work, or more likely be the kinds of embarrassing failures people would gather together and talk about until the end of time. They always had that in common: looking back at them, people explain why they were inevitable successes. While I was doing them, I had no idea.

I still don’t. And where would be the fun in making something you knew was going to work?

And sometimes the things I did really didn’t work. There are stories of mine that have never been reprinted. Some of them never even left the house. But I learned as much from them as I did from the things that worked.

Sixthly, I will pass on some secret freelancer knowledge. Secret knowledge is always good. And it is useful for anyone who ever plans to create art for other people, to enter a freelance world of any kind. I learned it in comics, but it applies to other fields too. And it’s this:

People get hired because, somehow, they get hired. In my case I did something which these days would be easy to check, and would get me into trouble, and when I started out, in those pre-internet days, seemed like a sensible career strategy: when I was asked by editors who I’d worked for, I lied. I listed a handful of magazines that sounded likely, and I sounded confident, and I got jobs. I then made it a point of honour to have written something for each of the magazines I’d listed to get that first job, so that I hadn’t actually lied, I’d just been chronologically challenged… You get work however you get work.

People keep working, in a freelance world, and more and more of today’s world is freelance, because their work is good, and because they are easy to get along with, and because they deliver the work on time. And you don’t even need all three. Two out of three is fine. People will tolerate how unpleasant you are if your work is good and you deliver it on time. They’ll forgive the lateness of the work if it’s good, and if they like you. And you don’t have to be as good as the others if you’re on time and it’s always a pleasure to hear from you.

When I agreed to give this address, I started trying to think what the best advice I’d been given over the years was.

And it came from Stephen King twenty years ago, at the height of the success of Sandman. I was writing a comic that people loved and were taking seriously. King had liked Sandman and my novel with Terry Pratchett, Good Omens, and he saw the madness, the long signing lines, all that, and his advice was this:

“This is really great. You should enjoy it.”

And I didn’t. Best advice I got that I ignored.Instead I worried about it. I worried about the next deadline, the next idea, the next story. There wasn’t a moment for the next fourteen or fifteen years that I wasn’t writing something in my head, or wondering about it. And I didn’t stop and look around and go, this is really fun. I wish I’d enjoyed it more. It’s been an amazing ride. But there were parts of the ride I missed, because I was too worried about things going wrong, about what came next, to enjoy the bit I was on.

That was the hardest lesson for me, I think: to let go and enjoy the ride, because the ride takes you to some remarkable and unexpected places.

And here, on this platform, today, is one of those places. (I am enjoying myself immensely.)

To all today’s graduates: I wish you luck. Luck is useful. Often you will discover that the harder you work, and the more wisely you work, the luckier you get. But there is luck, and it helps.

We’re in a transitional world right now, if you’re in any kind of artistic field, because the nature of distribution is changing, the models by which creators got their work out into the world, and got to keep a roof over their heads and buy sandwiches while they did that, are all changing. I’ve talked to people at the top of the food chain in publishing, in bookselling, in all those areas, and nobody knows what the landscape will look like two years from now, let alone a decade away. The distribution channels that people had built over the last century or so are in flux for print, for visual artists, for musicians, for creative people of all kinds.

Which is, on the one hand, intimidating, and on the other, immensely liberating. The rules, the assumptions, the now-we’re supposed to’s of how you get your work seen, and what you do then, are breaking down. The gatekeepers are leaving their gates. You can be as creative as you need to be to get your work seen. YouTube and the web (and whatever comes after YouTube and the web) can give you more people watching than television ever did. The old rules are crumbling and nobody knows what the new rules are.

So make up your own rules.

Someone asked me recently how to do something she thought was going to be difficult, in this case recording an audio book, and I suggested she pretend that she was someone who could do it. Not pretend to do it, but pretend she was someone who could. She put up a notice to this effect on the studio wall, and she said it helped.

So be wise, because the world needs more wisdom, and if you cannot be wise, pretend to be someone who is wise, and then just behave like they would.

And now go, and make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious and fantastic mistakes. Break rules. Leave the world more interesting for your being here. Make good art.

The Unique Challenges of Women in Leadership

Barack Obama

Barnard College, New York City, USA

MAY 14, 2012

President Obama was a 1983 graduate of Columbia College, Barnard’s big brother. He later graduated from Harvard Law School and then tried to find a career in public service.

Thank you, President Spar, trustees, President Bollinger. Hello, Class of 2012! Congratulations on reaching this day. Thank you for the honor of being able to be a part of it.

There are so many people who are proud of you – your parents, family, faculty, friends – all who share in this achievement. So please give them a big round of applause. To all the moms who are here today, you could not ask for a better Mother’s Day gift than to see all of these folks graduate.

I have to say, though, whenever I come to these things, I start thinking about Malia and Sasha graduating, and I start tearing up and – I don’t know how you guys are holding it together.

I will begin by telling a hard truth: I’m a Columbia college graduate. I know there can be a little bit of a sibling rivalry here. But I’m honored nevertheless to be your commencement speaker today – although I’ve got to say, you set a pretty high bar given the past three years. Hillary Clinton, Meryl Streep, Sheryl Sandberg – these are not easy acts to follow.

But I will point out Hillary is doing an extraordinary job as one of the finest Secretaries of State America has ever had. We gave Meryl the Presidential Medal of Arts and Humanities. Sheryl is not just a good friend; she’s also one of our economic advisers. So it’s like the old saying goes – keep your friends close, and your Barnard commencement speakers even closer. There’s wisdom in that.

Now, the year I graduated – this area looks familiar – the year I graduated was 1983, the first year women were admitted to Columbia. Sally Ride was the first American woman in space. Music was all about Michael and the Moonwalk. (Audience member: “Do it!”) No Moonwalking. No Moonwalking today.

We had the Walkman, not iPods. Some of the streets around here were not quite so inviting. Times Square was not a family destination. So I know this is all ancient history. Nothing worse than commencement speakers droning on about bygone days. But for all the differences, the Class of 1983 actually had a lot in common with all of you. For we, too, were heading out into a world at a moment when our country was still recovering from a particularly severe economic recession. It was a time of change. It was a time of uncertainty. It was a time of passionate political debates.

You can relate to this because just as you were starting out finding your way around this campus, an economic crisis struck that would claim more than 5 million jobs before the end of your freshman year. Since then, some of you have probably seen parents put off retirement, friends struggle to find work. And you may be looking toward the future with that same sense of concern that my generation did when we were sitting where you are now.

Of course, as young women, you’re also going to grapple with some unique challenges, like whether you’ll be able to earn equal pay for equal work; whether you’ll be able to balance the demands of your job and your family; whether you’ll be able to fully control decisions about your own health.

And while opportunities for women have grown exponentially over the last 30 years, as young people, in many ways you have it even tougher than we did. This recession has been more brutal, the job losses steeper. Politics seems nastier. Congress more gridlocked than ever. Some folks in the financial world have not exactly been model corporate citizens.

No wonder that faith in our institutions has never been lower, particularly when good news doesn’t get the same kind of ratings as bad news anymore. Every day you receive a steady stream of sensationalism and scandal and stories with a message that suggest change isn’t possible; that you can’t make a difference; that you won’t be able to close that gap between life as it is and life as you want it to be.

My job today is to tell you don’t believe it. Because as tough as things have been, I am convinced you are tougher. I’ve seen your passion and I’ve seen your service. I’ve seen you engage and I’ve seen you turn out in record numbers. I’ve heard your voices amplified by creativity and a digital fluency that those of us in older generations can barely comprehend. I’ve seen a generation eager, impatient even, to step into the rushing waters of history and change its course.

And that defiant, can-do spirit is what runs through the veins of American history. It’s the lifeblood of all our progress. And it is that spirit which we need your generation to embrace and rekindle right now.

See, the question is not whether things will get better – they always do. The question is not whether we’ve got the solutions to our challenges – we’ve had them within our grasp for quite some time. We know, for example, that this country would be better off if more Americans were able to get the kind of education that you’ve received here at Barnard – if more people could get the specific skills and training that employers are looking for today.

We know that we’d all be better off if we invest in science and technology that sparks new businesses and medical breakthroughs; if we developed more clean energy so we could use less foreign oil and reduce the carbon pollution that’s threatening our planet.

We know that we’re better off when there are rules that stop big banks from making bad bets with other people’s money and – when insurance companies aren’t allowed to drop your coverage when you need it most or charge women differently from men. Indeed, we know we are better off when women are treated fairly and equally in every aspect of American life – whether it’s the salary you earn or the health decisions you make.

After decades of slow, steady, extraordinary progress, you are now poised to make this the century where women shape not only their own destiny but the destiny of this nation and of this world.

We know these things to be true. We know that our challenges are eminently solvable. The question is whether together, we can muster the will – in our own lives, in our common institutions, in our politics – to bring about the changes we need. And I’m convinced your generation possesses that will. And I believe that the women of this generation, that all of you will help lead the way.

Now, I recognize that’s a cheap applause line when you’re giving a commencement at Barnard. It’s the easy thing to say. But it’s true. It is, in part, simple math. Today, women are not just half this country; you’re half its workforce. More and more women are out-earning their husbands. You’re more than half of our college graduates, and master’s graduates, and PhDs. So you’ve got us outnumbered.

After decades of slow, steady, extraordinary progress, you are now poised to make this the century where women shape not only their own destiny but the destiny of this nation and of this world.

But how far your leadership takes this country, how far it takes this world – well, that will be up to you. You’ve got to want it. It will not be handed to you. And as someone who wants that future, that better future, for you, and for Malia and Sasha, as somebody who’s had the good fortune of being the husband and the father and the son of some strong, remarkable women, allow me to offer just a few pieces of advice. That’s obligatory. Bear with me.

My first piece of advice is this: Don’t just get involved. Fight for your seat at the table. Better yet, fight for a seat at the head of the table.

It’s been said that the most important role in our democracy is the role of citizen. And indeed, it was 225 years ago today that the Constitutional Convention opened in Philadelphia, and our founders, citizens all, began crafting an extraordinary document. Yes, it had its flaws, flaws that this nation has strived to correct over time. Questions of race and gender were unresolved. No woman’s signature graced the original document – although we can assume that there were founding mothers whispering smarter things in the ears of the founding fathers. I mean, that’s almost certain.

What made this document special was that it provided the space, the possibility, for those who had been left out of our charter to fight their way in. It provided people the language to appeal to principles and ideals that broadened democracy’s reach. It allowed for protest, and movements, and the dissemination of new ideas that would repeatedly, decade after decade, change the world – a constant forward movement that continues to this day.

Our founders understood that America does not stand still; we are dynamic, not static. We look forward, not back. And now that new doors have been opened for you, you’ve got an obligation to seize those opportunities.

You need to do this not just for yourself but for those who don’t yet enjoy the choices that you’ve had, the choices you will have. And one reason many workplaces still have outdated policies is because women only account for 3 percent of the CEOs at Fortune 500 companies. One reason we’re actually refighting long-settled battles over women’s rights is because women occupy fewer than one in five seats in Congress.

Now, I’m not saying that the only way to achieve success is by climbing to the top of the corporate ladder or running for office, although, let’s face it, Congress would get a lot more done if you did. That I think we’re sure about. But if you decide not to sit yourself at the table, at the very least you’ve got to make sure you have a say in who does. It matters.

Before women like Barbara Mikulski and Olympia Snowe and others got to Congress, just to take one example, much of federally-funded research on diseases focused solely on their effects on men. It wasn’t until women like Patsy Mink and Edith Green got to Congress and passed Title IX, 40 years ago this year, that we declared women, too, should be allowed to compete and win on America’s playing fields. Until a woman named Lilly Ledbetter showed up at her office and had the courage to step up and say, you know what, this isn’t right, women weren’t being treated fairly – we lacked some of the tools we needed to uphold the basic principle of equal pay for equal work.

So don’t accept somebody else’s construction of the way things ought to be. It’s up to you to right wrongs. It’s up to you to point out injustice. It’s up to you to hold the system accountable and sometimes upend it entirely. It’s up to you to stand up and to be heard, to write and to lobby, to march, to organize, to vote. Don’t be content to just sit back and watch.

Those who oppose change, those who benefit from an unjust status quo, have always bet on the public’s cynicism or the public’s complacency. Throughout American history, though, they have lost that bet, and I believe they will this time as well. But ultimately, Class of 2012, that will depend on you. Don’t wait for the person next to you to be the first to speak up for what’s right. Because maybe, just maybe, they’re waiting on you.

Which brings me to my second piece of advice: Never underestimate the power of your example. The very fact that you are graduating, let alone that more women now graduate from college than men, is only possible because earlier generations of women – your mothers, your grandmothers, your aunts – shattered the myth that you couldn’t or shouldn’t be where you are.

I think of a friend of mine who’s the daughter of immigrants. When she was in high school, her guidance counselor told her, you know what, you’re just not college material. You should think about becoming a secretary. Well, she was stubborn, so she went to college anyway. She got her master’s. She ran for local office, won. She ran for state office, she won. She ran for Congress, she won. And lo and behold, Hilda Solis did end up becoming a secretary – she is America’s Secretary of Labor.

So think about what that means to a young Latina girl when she sees a Cabinet secretary that looks like her. Think about what it means to a young girl in Iowa when she sees a presidential candidate who looks like her. Think about what it means to a young girl walking in Harlem right down the street when she sees a U.N. ambassador who looks like her. Do not underestimate the power of your example.

This diploma opens up new possibilities, so reach back, convince a young girl to earn one, too. If you earned your degree in areas where we need more women – like computer science or engineering – reach back and persuade another student to study it, too. If you’re going into fields where we need more women, like construction or computer engineering – reach back, hire someone new. Be a mentor. Be a role model.

Until a girl can imagine herself, can picture herself as a computer programmer, or a combatant commander, she won’t become one. Until there are women who tell her, ignore our pop culture obsession over beauty and fashion – and focus instead on studying and inventing and competing and leading, she’ll think those are the only things that girls are supposed to care about. Now, Michelle will say, nothing wrong with caring about it a little bit. You can be stylish and powerful, too. That’s Michelle’s advice.

And never forget that the most important example a young girl will ever follow is that of a parent. Malia and Sasha are going to be outstanding women because Michelle and Marian Robinson are outstanding women. So understand your power, and use it wisely.

My last piece of advice – this is simple, but perhaps most important: Persevere. Persevere. Nothing worthwhile is easy. No one of achievement has avoided failure – sometimes catastrophic failures. But they keep at it. They learn from mistakes. They don’t quit.

You know, when I first arrived on this campus, it was with little money, fewer options. But it was here that I tried to find my place in this world. I knew I wanted to make a difference, but it was vague how in fact I’d go about it. But I wanted to do my part to do my part to shape a better world.

So even as I worked after graduation in a few unfulfilling jobs here in New York – I will not list them all – even as I went from motley apartment to motley apartment, I reached out. I started to write letters to community organizations all across the country. And one day, a small group of churches on the South Side of Chicago answered, offering me work with people in neighborhoods hit hard by steel mills that were shutting down and communities where jobs were dying away.

The community had been plagued by gang violence, so once I arrived, one of the first things we tried to do was to mobilize a meeting with community leaders to deal with gangs. And I’d worked for weeks on this project. We invited the police; we made phone calls; we went to churches; we passed out flyers. The night of the meeting we arranged rows and rows of chairs in anticipation of this crowd. And we waited, and we waited. And finally, a group of older folks walked in to the hall and they sat down. And this little old lady raised her hand and asked, “Is this where the bingo game is?” It was a disaster. Nobody showed up. My first big community meeting – nobody showed up.

And later, the volunteers I worked with told me, that’s it; we’re quitting. They’d been doing this for two years even before I had arrived. They had nothing to show for it. And I’ll be honest, I felt pretty discouraged as well. I didn’t know what I was doing. I thought about quitting. And as we were talking, I looked outside and saw some young boys playing in a vacant lot across the street. And they were just throwing rocks up at a boarded building. They had nothing better to do – late at night, just throwing rocks. And I said to the volunteers, “Before you quit, answer one question. What will happen to those boys if you quit? Who will fight for them if we don’t? Who will give them a fair shot if we leave?

And one by one, the volunteers decided not to quit. We went back to those neighborhoods and we kept at it. We registered new voters, and we set up after-school programs, and we fought for new jobs, and helped people live lives with some measure of dignity. And we sustained ourselves with those small victories. We didn’t set the world on fire. Some of those communities are still very poor. There are still a lot of gangs out there. But I believe that it was those small victories that helped me win the bigger victories of my last three and a half years as President.

And I wish I could say that this perseverance came from some innate toughness in me. But the truth is, it was learned. I got it from watching the people who raised me. More specifically, I got it from watching the women who shaped my life.

I grew up as the son of a single mom who struggled to put herself through school and make ends meet. She had marriages that fell apart; even went on food stamps at one point to help us get by. But she didn’t quit. And she earned her degree, and made sure that through scholarships and hard work, my sister and I earned ours. She used to wake me up when we were living overseas, wake me up before dawn to study my English lessons. And when I’d complain, she’d just look at me and say, “This is no picnic for me either, buster.”

And my mom ended up dedicating herself to helping women around the world access the money they needed to start their own businesses – she was an early pioneer in microfinance. And that meant, though, that she was gone a lot, and she had her own struggles trying to figure out balancing motherhood and a career. And when she was gone, my grandmother stepped up to take care of me.

She only had a high school education. She got a job at a local bank. She hit the glass ceiling, and watched men she once trained promoted up the ladder ahead of her. But she didn’t quit. Rather than grow hard or angry each time she got passed over, she kept doing her job as best as she knew how, and ultimately ended up being vice president at the bank. She didn’t quit.

And later on, I met a woman who was assigned to advise me on my first summer job at a law firm. And she gave me such good advice that I married her. And Michelle and I gave everything we had to balance our careers and a young family. But let’s face it, no matter how enlightened I must have thought myself to be, it often fell more on her shoulders when I was traveling, when I was away. I know that when she was with our girls, she’d feel guilty that she wasn’t giving enough time to her work, and when she was at her work, she’d feel guilty she wasn’t giving enough time to our girls. And both of us wished we had some superpower that would let us be in two places at once. But we persisted. We made that marriage work.

And the reason Michelle had the strength to juggle everything, and put up with me and eventually the public spotlight, was because she, too, came from a family of folks who didn’t quit – because she saw her dad get up and go to work every day even though he never finished college, even though he had crippling MS. She saw her mother, even though she never finished college, in that school, that urban school, every day making sure Michelle and her brother were getting the education they deserved. Michelle saw how her parents never quit. They never indulged in self-pity, no matter how stacked the odds were against them. They didn’t quit.

Those are the folks who inspire me. People ask me sometimes, who inspires you, Mr. President? Those quiet heroes all across this country – some of your parents and grandparents who are sitting here – no fanfare, no articles written about them, they just persevere. They just do their jobs. They meet their responsibilities. They don’t quit. I’m only here because of them. They may not have set out to change the world, but in small, important ways, they did. They certainly changed mine.

So whether it’s starting a business, or running for office, or raising a amazing family, remember that making your mark on the world is hard. It takes patience. It takes commitment. It comes with plenty of setbacks and it comes with plenty of failures.

But whenever you feel that creeping cynicism, whenever you hear those voices say you can’t make a difference, whenever somebody tells you to set your sights lower – the trajectory of this country should give you hope. Previous generations should give you hope. What young generations have done before should give you hope. Young folks who marched and mobilized and stood up and sat in, from Seneca Falls to Selma to Stonewall, didn’t just do it for themselves; they did it for other people.

That’s how we achieved women’s rights. That’s how we achieved voting rights. That’s how we achieved workers’ rights. That’s how we achieved gay rights. That’s how we’ve made this Union more perfect.

And if you’re willing to do your part now, if you’re willing to reach up and close that gap between what America is and what America should be, I want you to know that I will be right there with you. If you are ready to fight for that brilliant, radically simple idea of America that no matter who you are or what you look like, no matter who you love or what God you worship, you can still pursue your own happiness, I will join you every step of the way.

Now more than ever – now more than ever, America needs what you, the Class of 2012, has to offer. America needs you to reach high and hope deeply. And if you fight for your seat at the table, and you set a better example, and you persevere in what you decide to do with your life, I have every faith not only that you will succeed, but that, through you, our nation will continue to be a beacon of light for men and women, boys and girls, in every corner of the globe.

So thank you. Congratulations. God bless you. God bless the United States of America.